At Jisc’s Learning Analytics Network meeting last month I presented an updated version of my suggested legal model for Learning Analytics. The new version adds the data collection stage(s) and seems to me – both as a sometime system developer and privacy-sensitive student – to provide the kinds of guidance, choices and protections that I’d expect universities and colleges to apply to student data.

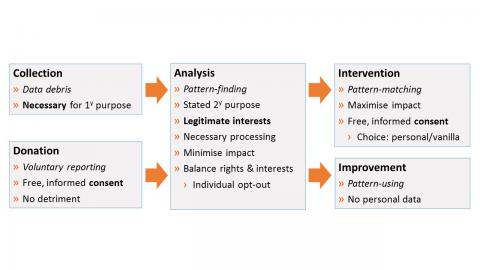

Whereas learning analytics has sometimes been documented as a monolithic process, it seems to fit much better into data protection law if split into (up to) five separate stages:

- Data Collection: using information the institution has already gathered about students as part of existing educational processes. Here rules and guidance on necessity and purpose limitation can help determine what data may be used for learning analytics purposes and how far those purposes may extend;

- Data Donation (optional): in some cases students may be asked to provide additional information – for example reporting on their own study patterns. Rules and guidance on consent indicate what information students must be given and the rights they have to refuse or stop providing information without detriment;

- Analysis: the stage where data are interrogated to discover relevant patterns, highlighting factors that may improve or hinder educational achievement. During this stage the aim should be to minimise impact on individuals and ensure that any remaining risk is justified, in accordance with rules and guidance on processing for legitimate interests;

- Improvement (optional): where patterns can be used to improve educational provision in general, for example by adapting teaching materials or practices. Here there is no need to process personal data at all;

- Intervention (optional): where patterns are used to identify and propose relevant actions for individual students. Here personal data must be used, and the aim is to maximise the (positive) impact on individuals. Thus consent for interventions is needed (unless they are, for example, a legal obligation) and this can be sought at the time when the organisation can give the most detailed information about the proposed intervention and its likely consequences.

It was good to receive feedback that this model was “reassuring” and, indeed, matched what many organisations already do in practice, even though their policies may describe the simpler, monolithic, model. The legal detail and resulting guidance can be found in a paper: “Downstream Consent: A Better Legal Framework for Big Data”, published in the Journal of Information Rights, Policy and Practice.